BELLOWS, SMOKE & ELECTRICITY

In 1744, William Tossach described mouth-to-mouth resuscitation he’d performed on a coal miner. His description raised questions about using bellows instead of direct contact. The idea was dismissed and not raised again for 30 years.

Richard Mead suggested, in 1747, warmth, friction and blowing tobacco smoke into the rectum for resuscitation. The nicotine was thought to stimulate the heart to beat stronger and faster, encouraging respiration. The smoke was also thought to warm the victim and dry out the person’s insides, removing excessive moisture.

John Wilkinson published a suggestion in a 1764 book dedicated to preserving drowned seamen, that hot pointed irons and electricity were potentially useful. Ten years later, William Cullen suggested bellows could be used for “persons drowned and seemingly dead”.

The Royal Humane Society officially endorsed bellows in 1782, along with a broader range of Dutch methods including warming, rubbing, mouth-to-mouth, and tobacco smoke enemas. Several specialised resuscitation kits were developed and distributed during the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

BELLOWS AND SELF-INFLATING BAGS

Frenchman, Jean Leroy demonstrated in 1827 that bellows could cause emphysema and pneumothorax. The French Academy of Science endorsed his finding in 1832. Soon after, the Royal Humane Society withdrew support as well, recommending manual resuscitation methods.

Over a century later, American anesthesiologist, Joseph Kreiselman reintroduced bellows with a new resuscitation apparatus.

Many variations on the theme were to follow but by the 1970s, the clinical value of self-inflating resuscitation bags had been well established.

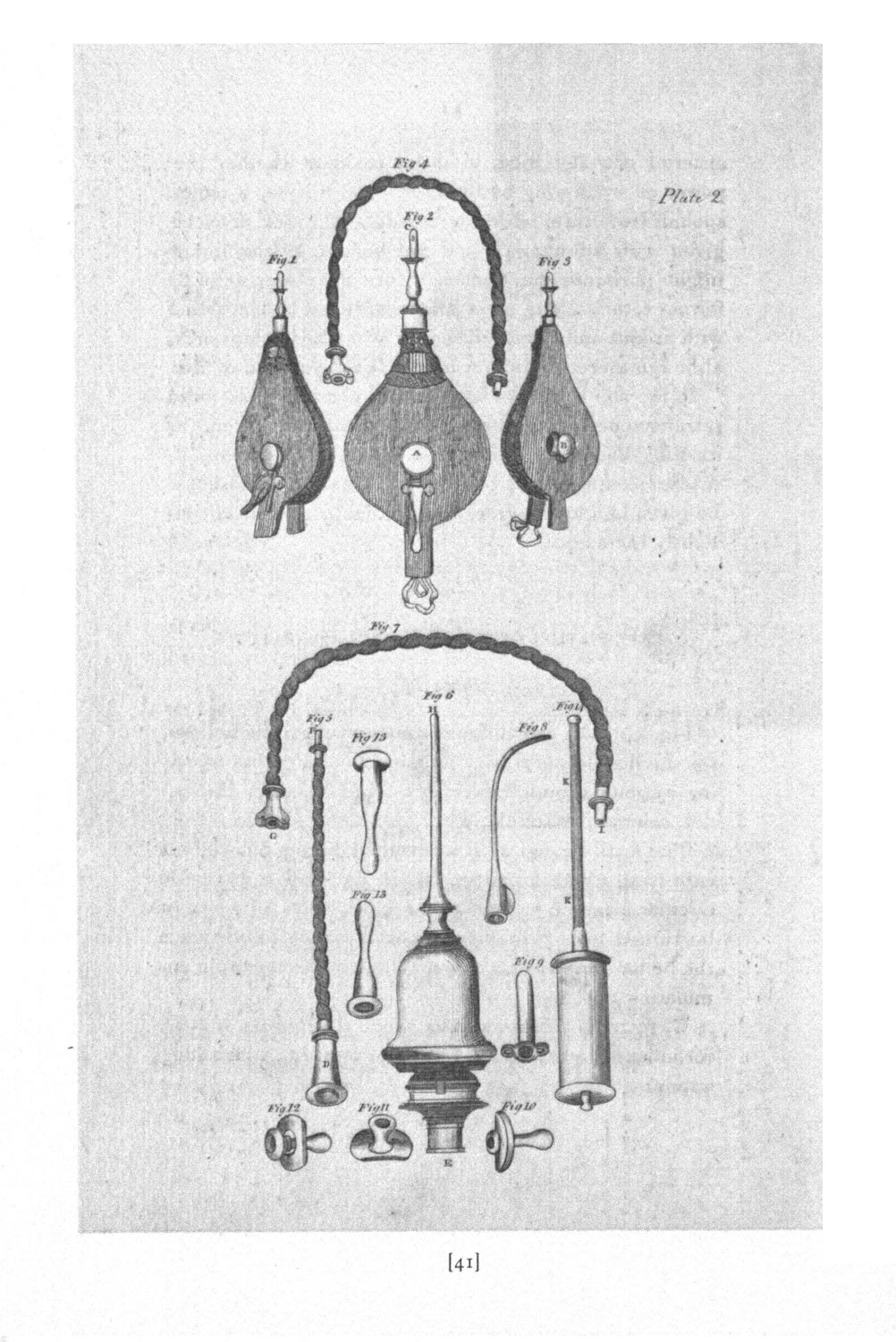

Images above: Bellows apparatus, courtesy Wood Library-Museum, of Anesthesiology, Schaumburg, Illinois

Image left: Surgical instruments, including bellows for inflating the lungs. Engraving by Andrew Bell. Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence. Wellcome Library, London.

FUMIGATION RESUSCITATION

D.M.P. Bourgery’s 1833 book carries a chapter on fumigation methods and apparatus, including use of a fumigation box, bottle, bellows and pyramid. He suggests the ear, nose, throat, vagina and rectum are all suitable for fumigation treatments.

Image: A Treatise on Lesser Surgery; or, the minor surgical operations by D.M.P. Bourgery, 1833

PORTON RESUSCITATOR

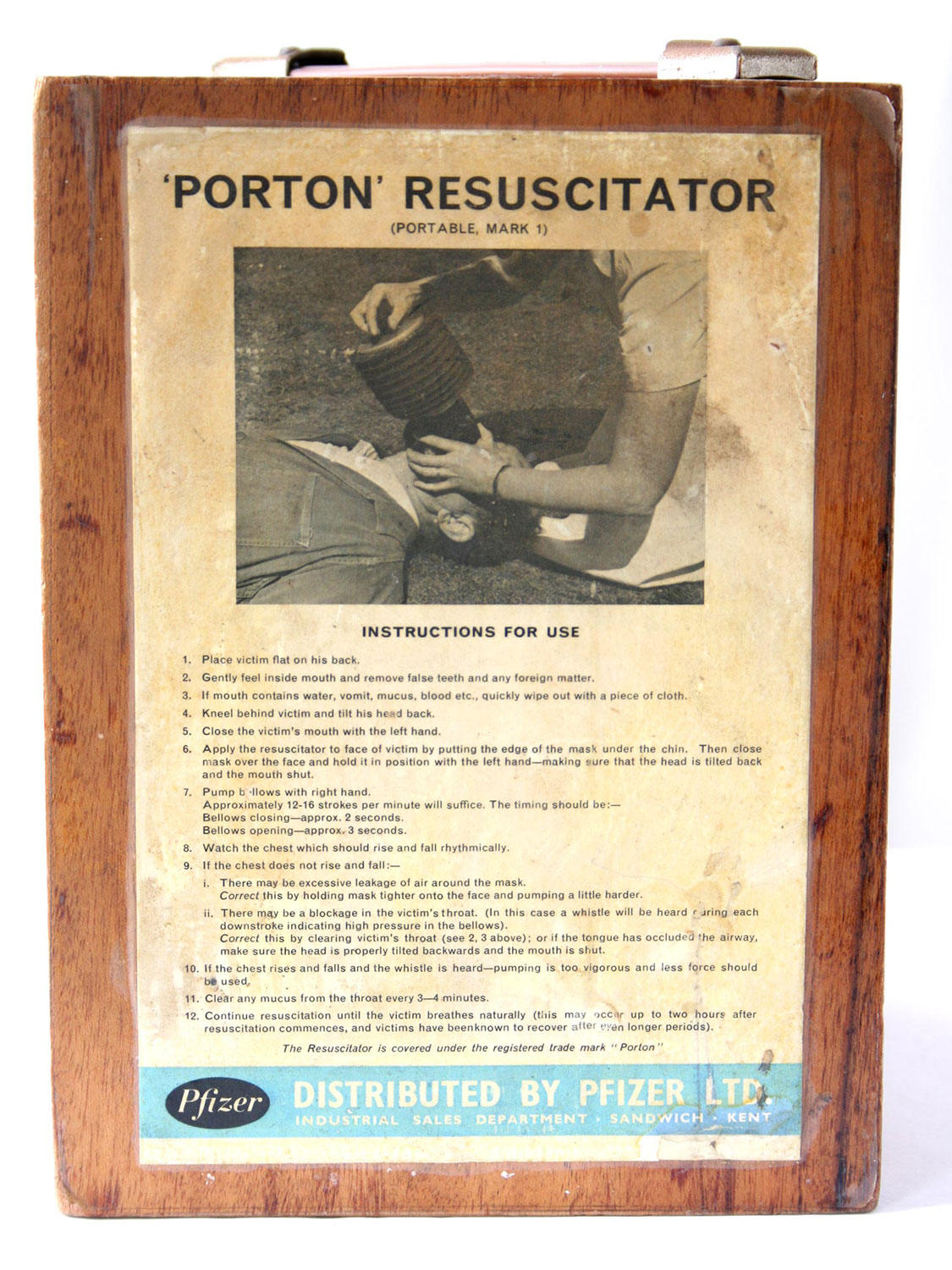

The Porton resuscitator was devised in 1951 at the British Chemical Defence Experimental Establishment in Porton, Salisbury, as a bellows-valve-mask resuscitator. Extensive testing was undertaken over eight years, with the device being successfully used for air transport of polio patients, for emergency resuscitation in hospital wards, and by hospital orderlies.

Image: Porton resuscitator in original box, c1951

AMBU BAG RESUSCITATOR

During a 1954 transport strike, Danish hospitals couldn’t receive oxygen deliveries. In Copenhagen, Henning Ruben created a resuscitator with the look and feel of an anaesthetic “bag-and-mask”. It didn’t require compressed oxygen. Testa-Laboratorium agreed to market the resuscitator with some modifications, including the ability to operate the bag by foot.

Image: Ambu bag resuscitator, 1961

EXPIRED-AIR RESUSCITATION

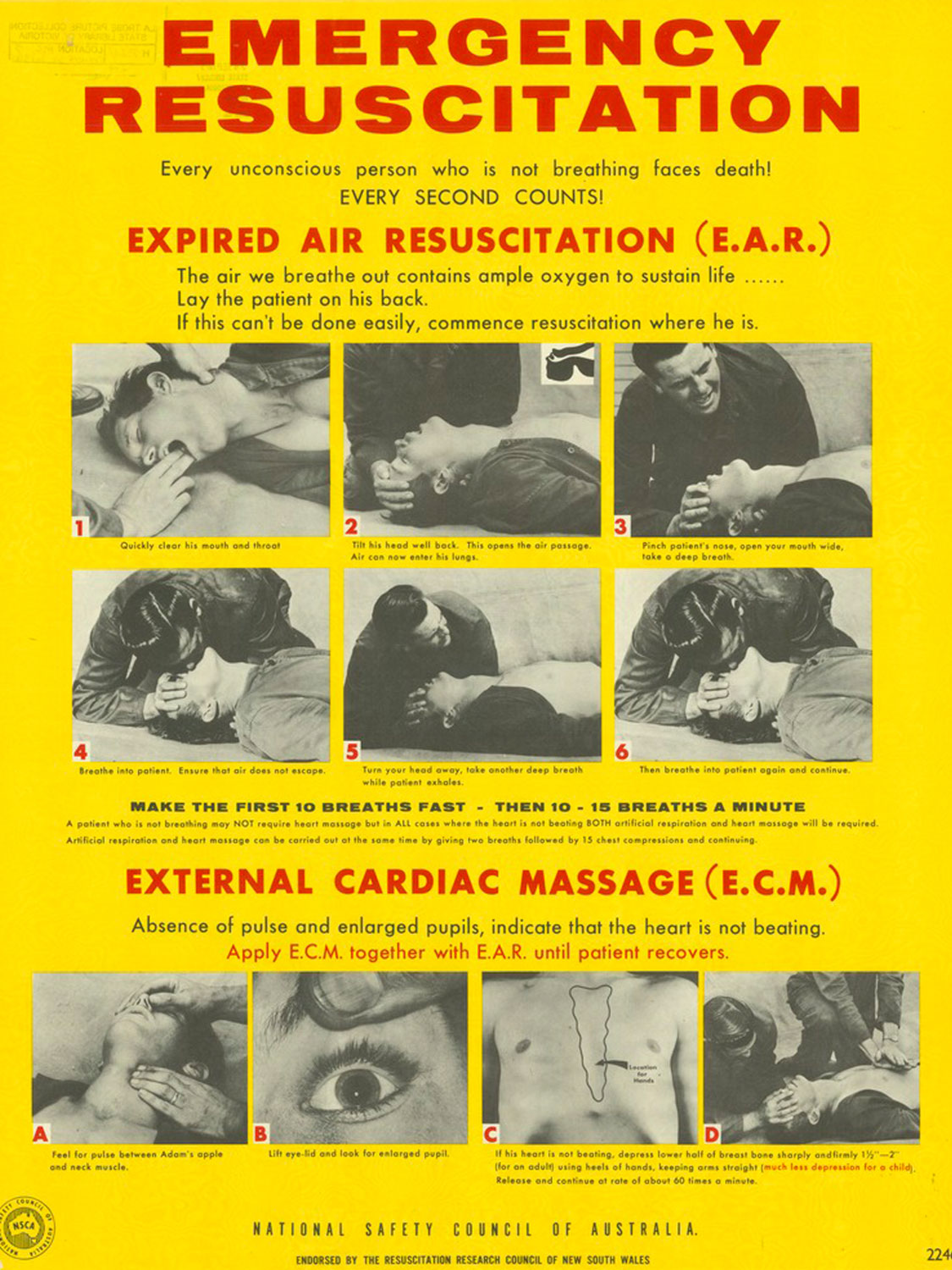

On 1 June, 1959, the Australian Broadcasting Commission screened a documentary showing experiments with mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. It showed a volunteer “patient” anaesthetised, paralysed and connected to a large spirometer via a taped-on facemask. Various indirect methods of resuscitation were attempted. Dr Bruce Clifton, an anaesthetist, then performed mouth-to-mouth. It was soon apparent expired-air resuscitation was far more effective than previously used, indirect methods of resuscitation.

Image: Emergency Resuscitation Poster, National Safety Council of Australia, c1970-c1980. State Library Victoria collection.

ORAL AIRWAYS

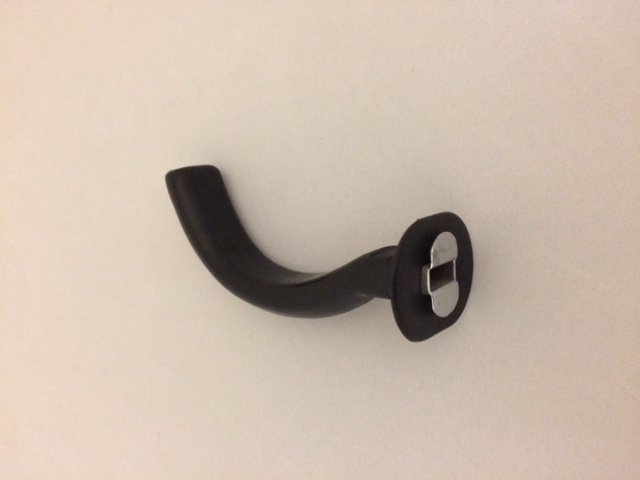

Oral airways, such as the Guedel, make it much easier for patients to be ventilated with manual resuscitators, such as the Porton and the Ambu bag. They depress the tongue and prevent it from falling to the back of the throat where it would obstruct the airway.

Image: Guedel pharyngeal airway

SURF LIFE SAVING AND MOUTH-TO-MOUTH RESUSCITATION

The mouth-to-mouth experiment findings were reported at the International Convention of Life Saving Techniques in Sydney in 1960, and in the 1968 RLSSA instruction manual. The issue then became how to make it acceptable, how to teach it, and how it should be applied.

Image: Manual of Water Safety and Life-Saving, The Royal Life-Saving Society, Australia, 1969 (on loan from Dr CM Ball)

OXYGEN AND POSITIVE PRESSURE DEVICES

Gas lighting to houses led to an increase in cases of carbon monoxide poisoning. Mining accidents were also increasingly common. In both cases oxygen was recognised as important in the resuscitation process. Oxygen became available in cylinders in the 1870s and its availability was probably largely responsible for the resurgence of positive pressure resuscitation devices in the early 20th century. Positive pressure devices deliver air or oxygen into the lungs at a rate determined by the operator.

The Dräeger Pulmotor was developed in 1907. It addressed previous concerns about lung injury, by limiting both the inspiratory and expiratory pressures. Although still controversial, the Pulmotor was widely distributed and commercially successful. Oxygen from cylinders provided both the inspiratory gas flow and the driving mechanism. Expiration was an active process and gases were sucked from the lungs by negative pressure created by a Venturi effect. This device came with a facemask and harness, with a caution that the operator should take care to prevent air entering the stomach.

DRÄEGER PULMOTOR

The Dräeger Pulmotor was designed in 1907, and addressed concerns about lung injury. It limited the inspiratory pressure on the lungs. Expiration was an active process and gases were sucked from the lungs by negative pressure, created by a Venturi effect.

Image: Dräeger Pulmotor, c1920

ARTIFICIAL RESPIRATION FILM, 1927

“…have someone call a physician or the gas company…”

An old method of artificial respiration, CPR, that involves pushing on the back.

Courtesy of the Nurses of Los Angeles YouTube channel.

DEMONSTRATIONS OF H. N. METHOD, c1940s

This is a demonstration film showing the Holger-Neilson method of artificial respiration in cases of drowning. This method is demonstrated on a number of different subjects both male and female.

Courtesy of the Wellcome Library YouTube channel.