As the Australian military embarked, they took male nurses with them. Many of these had little more than two weeks training, instead of the three years of training required by civilian nurses.

Colonel Charles Ryan, Australia’s principal military medical officer, declared in August 1914 that nurses wouldn’t be needed.

Although this decision was quickly reversed, the sanction on women doctors remained. All avenues for military service were closed to them.

Other women, such as Dr Elsie Inglis who founded the Scottish Women’s Hospitals, also formed their own hospital units and facilities, staffed by women.

By the end of 1916 the Royal Army Medical Corps allowed women doctors. However, they were not afforded rank. While this granted entrance into military service for women doctors during WWI, the same arguments returned during World War II.

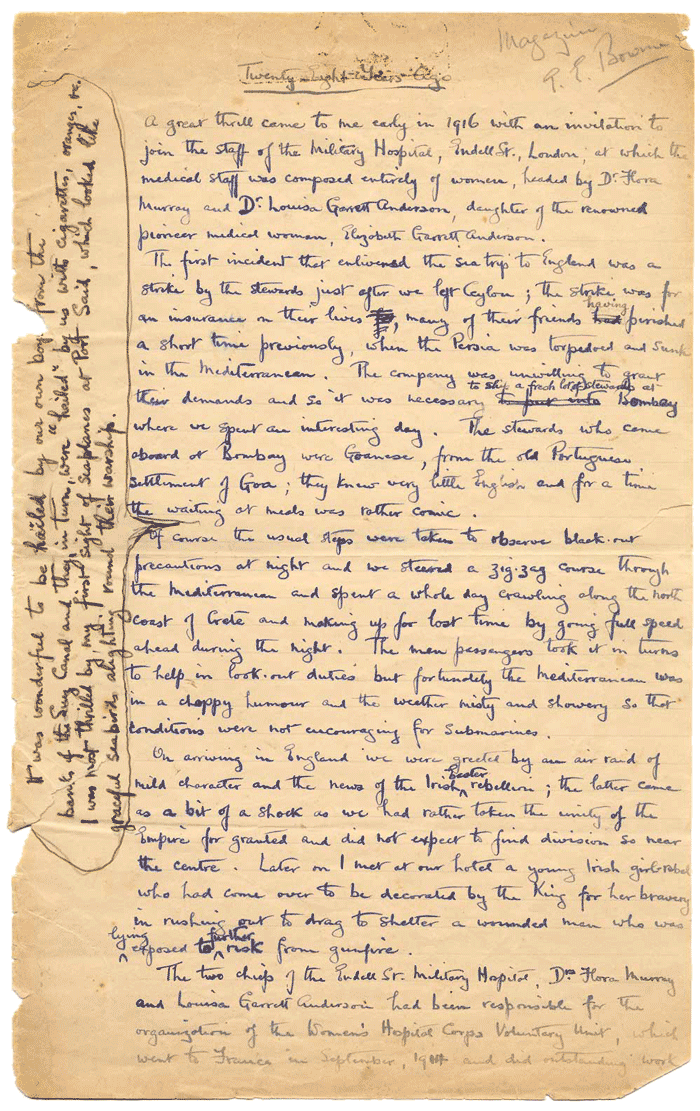

Dr Eleanor Elizabeth Bourne

MB ChM

On completion of her formal schooling Eleanor Elizabeth Bourne was awarded a government exhibition for university. She chose to study medicine.

As Queensland didn’t yet have a medical school, she enrolled at the University of Sydney. Eleanor Bourne was the first Queensland woman to study medicine.

During her studies she contracted typhoid and took a year off to recover, graduating MB ChM in 1903.

On returning to Brisbane, she was the first woman appointed to the Brisbane General Hospital, and was also at the Hospital for Sick Children.

Bourne was Honorary Anaesthetist at the Lady Lamington Hospital in Brisbane from 1907 – 1910. She simultaneously ran a general practice in Brisbane, and was Honorary Out-patient physician to the Children’s Hospital.

In 1911, she became the first medical officer in the Department of Public Health. Her work focused on children’s health.

In 1916 she travelled to England where she served at the Endell Street Hospital with the Royal Army Medical Corps. She was promoted in 1917 and transferred to Queen Mary’s Army Auxiliary Corps.

After completing a Diploma of Public Health at the Royal College of Physicians, Bourne resigned from her Queensland appointments. She retired in 1937 and returned to Brisbane.

Image: Eleanor Elizabeth Bourne. Image courtesy of State Library of Queensland, undated, photographer unknown.

The Endell Street Military Hospital was established in 1915 by Dr Flora Murray and Dr Louisa Garrett Anderson. Included in the photograph are the staff members of the hospital, including the women drivers, dentists, pathologists and surgeons. Eleanor Bourne is pictured in the second row, 10th from the right.

Image: Eleanor Bourne at the Endell Street Military Hospital. Image courtesy of the Women’s Library, London School of Economics & Political Science, 1916.

Eleanor Elizabeth Bourne describes her time at the Endell Street Military Hospital as “one of the highlights of my life”. She also details her trip from Ceylon to England, as well as providing insight into the daily life of some of the nurses and doctors at the hospital.

Document: Eleanor Bourne’s writings about being at Endell Street. Courtesy of State Library of Queensland, c1916 – 1918.

View handwritten document by clicking the document thumbnail, or read typed transcript here.

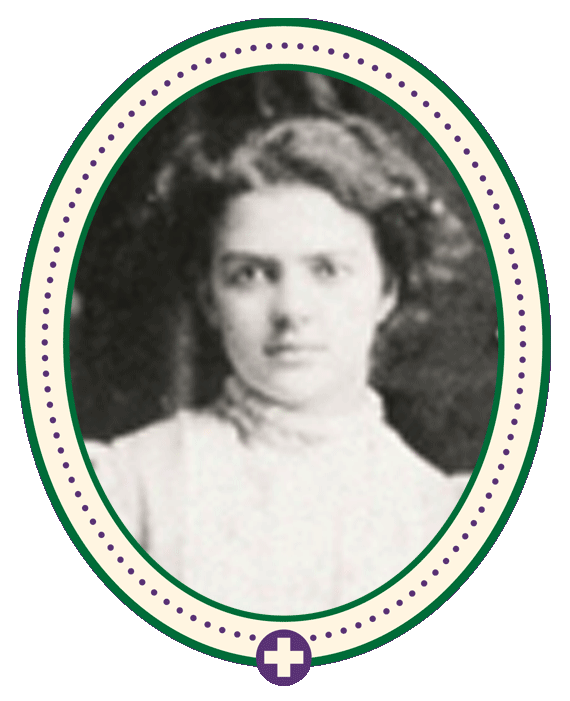

Dr Mary De Garis

MB BS, MD

In 1907, Mary Clementina De Garis became the second woman in Australia to be awarded MD. Despite her qualifications, residencies at prestigious hospitals, and glowing references, De Garis had difficulty finding work. Eventually, she secured a position at Muttaburra Hospital in outback Queensland.

She spent a little over a year there, and returned to Melbourne, setting up private practice in Collins Street. This proved unsustainable and she relocated to rural New South Wales. During her four years there, De Garis became engaged to local farmer, Colin Thomson.

With the outbreak of war, Thomson enlisted and was sent to Europe.

De Garis attempted to enlist with the Australian Imperial Force. She was rejected because the AIF wouldn’t accept women doctors. Instead, she moved to England to be closer to Thomson. Thomson was killed in action on 04 August 1916.

Heartbroken, De Garis joined the Scottish Women’s Hospitals for Foreign Service. She was awarded a Serbian Order of St Sava 3rd Class for her efforts in Serbia.

After the war, De Garis moved to Geelong. She championed maternal and perinatal health, campaigning for a maternity ward and antenatal clinic.

Mary De Garis continued to work at the Geelong Hospital until her retirement in 1958.

Image: Detail from Melbourne Hospital Residents, 1905-1906. Image courtesy Medical History Museum, University of Melbourne.

Owned by Dr Mary De Garis, this Minnitt anaesthetic machine was portable and relatively light weight. De Garis was able to take the machine wherever required, enabling women in labour to control their pain relief.

Robert James Minnitt introduced the concept of self-administered analgesia. The Minnitt apparatus met with considerable success and led to further modifications.

Image: Minnitt anaesthetic machine, from the collection of the Geoffrey Kaye Museum.

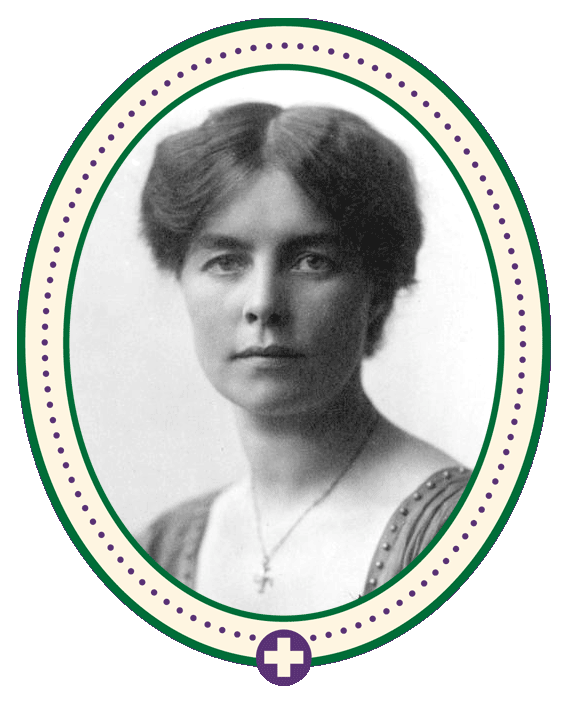

Dr Mary Alice Blair

MB BS, MD

Mary Alice Blair attained a Bachelor of Science from Auckland University College in 1902. Although six women had already graduated from medicine in New Zealand, she decided to undertake medical training at the London School of Medicine for Women.

The 1914 Medical Directory shows Blair graduated MB BS in 1907, and followed up with an MD in 1910.

Blair was appointed Honorary Anaesthetist at the Medical Mission Hospital Plaistow, which drew its patients from the Canning Town Women’s Settlement. She simultaneously established and maintained a private practice.

She joined the Scottish Women’s Hospitals for Foreign Service during World War I and left for Serbia in 1915. When forced to retreat, the unit worked in Salonica tending refugees and Blair organised a 100 bed hospital. When permission was granted to evacuate to Corsica, Blair accompanied them.

During 1916 she was contracted as a civilian surgeon to the Royal Army Medical Corps. Winston Churchill declared it impossible for women to take command should the need arise and they were therefore not afforded rank.

Blair continued to serve as a civilian medical practitioner with Queen Mary’s Army Auxiliary Corps at Isleworth Hospital through to 1919. Post war, she stayed in England, maintaining her private practice.

Scottish doctor Elsie Inglis gained her Licentiate of the Colleges of Physicians and Surgeons Edinburgh in 1892. In 1899 she was the first woman to graduate MB ChM from the University of Edinburgh.

When war broke out in 1914 she approached the War Office in Edinburgh, offering to co-ordinate women doctors either as part of the Royal Army Medical Corps or as separate women’s units.

The War Office responded, telling her, “My good lady, go home and sit still”.

Undeterred, Inglis founded the Scottish Women’s Hospitals for Foreign Service through the support of the Scottish Federation of Women Suffrage Societies, the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies, the Red Cross and other fund raising efforts.

The Scottish Women’s Hospitals provided nurses, doctors, ambulance drivers, cooks and orderlies to create 14 voluntary all women units that served in Corsica, France, Malta, Romania, Russia, Salonika and Serbia.

The Scottish Women’s Hospitals allowed women with medical training who were unable to enter the Royal Army Medical Corps to offer their skills for the war effort.

Qualified women doctors came from all over the British empire to offer their services to the Scottish Women’s Hospitals, including a significant number from Australia and New Zealand.

Image: The Scottish Women’s Hospital: In The Cloister of the Abbaye at Royaumont. Dr. Frances Ivens inspecting a French patient. Painting by Norah Neilson-Gray, who was an outstanding pupil at Glasgow School of Art, which she left to join the Scottish Women’s Hospital during the First World War. The painting is one of two commissioned in 1920 by the Imperial War Museum to commemorate the hospital and its leader Dr Frances Ivens. Image courtesy of the Imperial War Museum.

Dr Gweneth Wisewould

MB BS, MD

When Gweneth Wisewould graduated from medicine at the University of Melbourne in 1915 she was one of four women in a class of 50. With war raging, her medical skills were in high demand on the home front. For a short time she and her female colleagues received the same wage as male graduates.

As men returned from the war, the shortage of qualified medical men was no longer a problem. Women doctors’ wages quickly dropped to 75% of the male wage.

In 1917, Wisewould set up private practice in St Kilda, Elsternwick and the city. She was also performing surgery at the Queen Victoria Hospital and Senior Resident at the Queen’s Memorial Infectious Diseases Hospital. During 1918 – 1929 she instructed medical students at the Alfred Hospital in anaesthetics and held the position of anaesthetist there between 1920 and 1925.

In 1938, Wisewould was caught up in a controversy at the Queen Victoria Hospital. The nature of the controversy is still unclear but she left Melbourne and relocated to country Victoria.

At the time, Trentham was an isolated community, spread over rugged terrain. She worked as a general practitioner within that community until her death in 1972.