Many universities in Britain and America refused to admit women, although generally made concessions for arts and humanities. Occasionally women gained medical qualifications but the loopholes were then quickly closed. Some of these women opened their own medical colleges.

Australia and New Zealand followed a different path. The University of Sydney admitted Georgina Dagmar Berne to medicine in 1886. After a successful first year, the Dean of Medicine repeatedly failed her, and she had to move to England to complete her qualifications.

1891 also saw Emily Siedeberg admitted to medicine at the University of Otago. Small numbers of women followed, with three in 1904, and only one in each of 1902, 1903, 1906, 1910 and 1911.

The decline in women studying medicine in New Zealand, led newspapers of the day to incorrectly announce that “…the craze for women studying medicine had gone”.

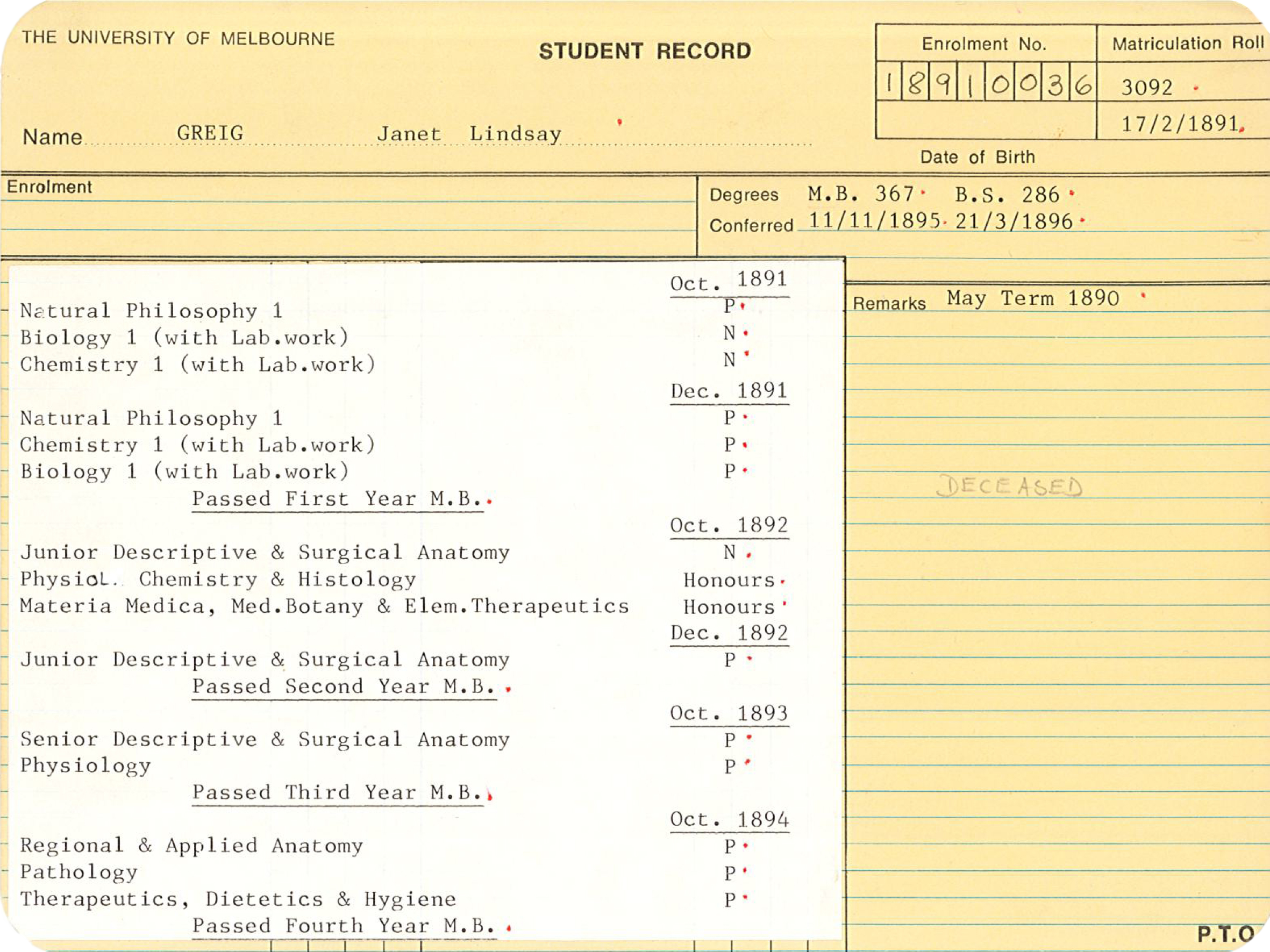

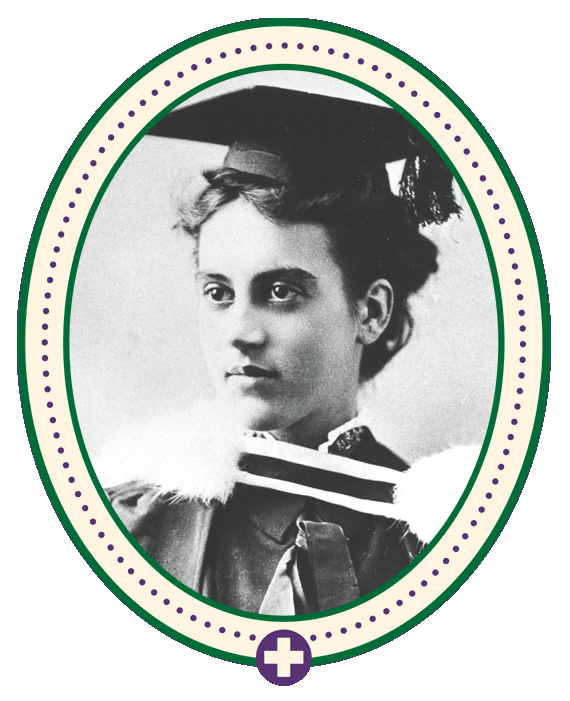

Dr Janet Greig

MB BS, MD

Janet Lindsay Greig was born in 1874 at Broughty Ferry, Scotland. She migrated to Melbourne with her family in 1889.

Greig graduated from medicine in 1896, finishing top six in her class, along with Alfreda Gamble. Traditionally, top six graduates automatically qualified for a residency at Melbourne General Hospital. The idea of women residents met with much opposition.

Eventually, hospital management voted 13 to six in favour of taking on the “Lady Graduates”.

After their residencies, the hospital’s chairman, Mr F. R. Godfrey conceded the women had been “…subjected to very unfair, ungentlemanly, and almost brutal conduct” at times.

In 1900 Greig was appointed Honorary Anaesthetist at the newly formed Queen Victoria Hospital. She was the first woman in Australia appointed to such a position. In 1903 she was also appointed Honorary Assistant Anaesthetist at the Melbourne General Hospital. Greig held both these positions until 1917, when she took up the more senior position of Honorary Physician at the Queen Victoria Hospital.

Greig was a foundation member of the Lyceum Club in 1912, and admitted as a Member of the Royal Australasian College of Physicians in 1940. She retired in 1948 and died on a visit to London in 1950.

Image: Photograph of Janet Greig from Gwen Wilson archive, original source unknown, c1896.

Janet Lindsay Greig qualified in medicine the same year as her sister Jane Stocks Greig. Grata Flos Matilda Greig was the first woman in Victoria to qualify in law, finishing second in her year, in 1903. Clara Puella Greig undertook a Bachelor of Science, although left the course to open a coaching college for students, engaging her women graduate friends as tutors. Stella Greig graduated from law in 1911.

Images: Janet Lindsay Greig student records. Image courtesy of the collection of the University of Melbourne.

Janet Greig and Ælfreda Gamble graduated from medicine in the top six at the University of Melbourne. A tradition had developed for the top six to be automatically offered a residency at Melbourne General Hospital. Nobody had really considered the possibility of women qualifying. Despite fierce opposition, the women steadfastly stood their ground and were the first women to be admitted to as residents at an Australian hospital.

“It is too late in the day to affirm or deny the advisability of admitting women to the practice of medicine, but it is not too late to protest against their elevation to places they cannot well fill. Their admission into the profession is sanctioned by widely established precedent, and still leaves the public free to accept or reject their medical advice; but their establishment as Hospital Residents is a step decidedly more serious.”

Image: Speculum, A Journal of the Melbourne Medical Students Society, Article, 1896. Image courtesy of the University of Melbourne Archives.

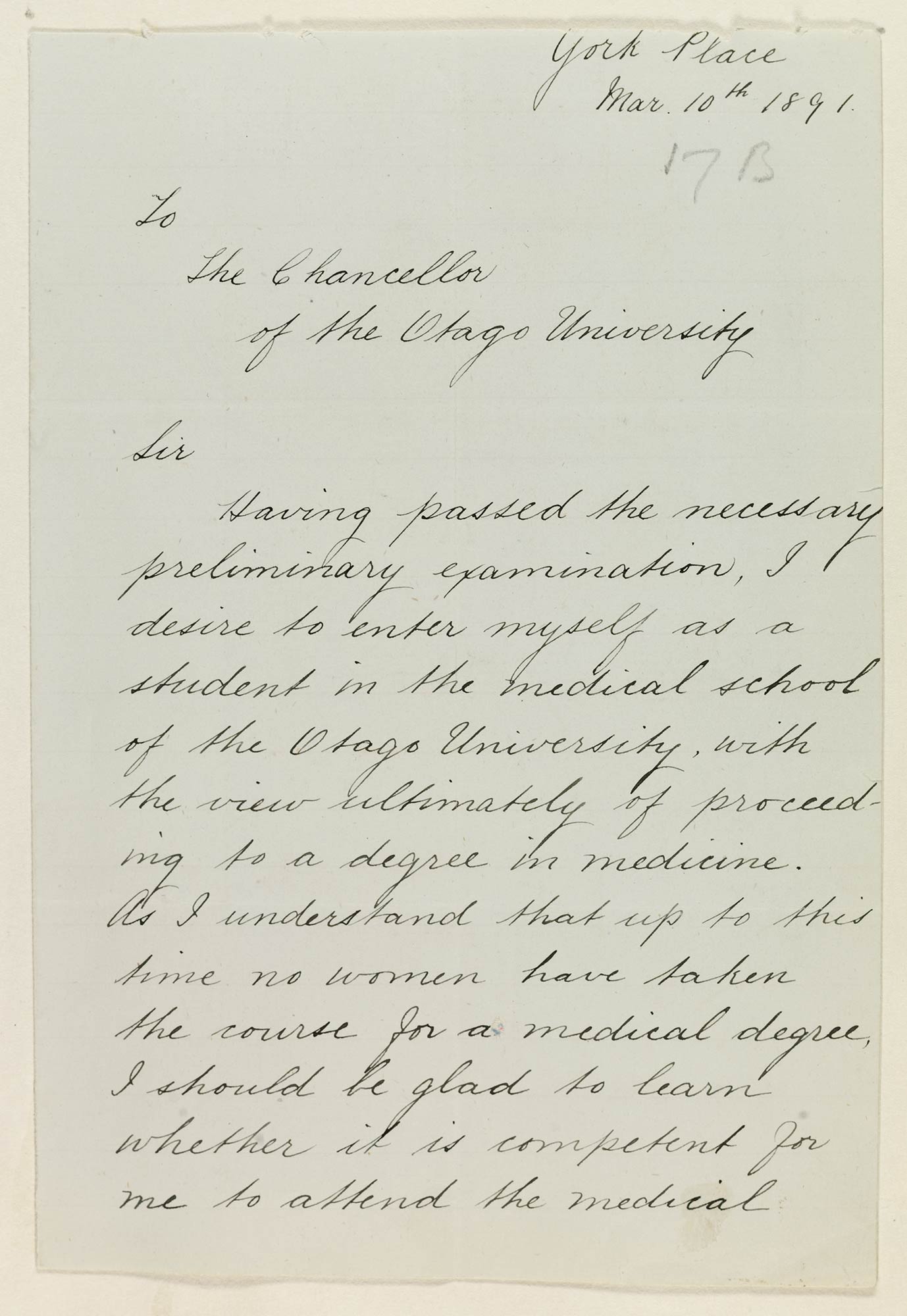

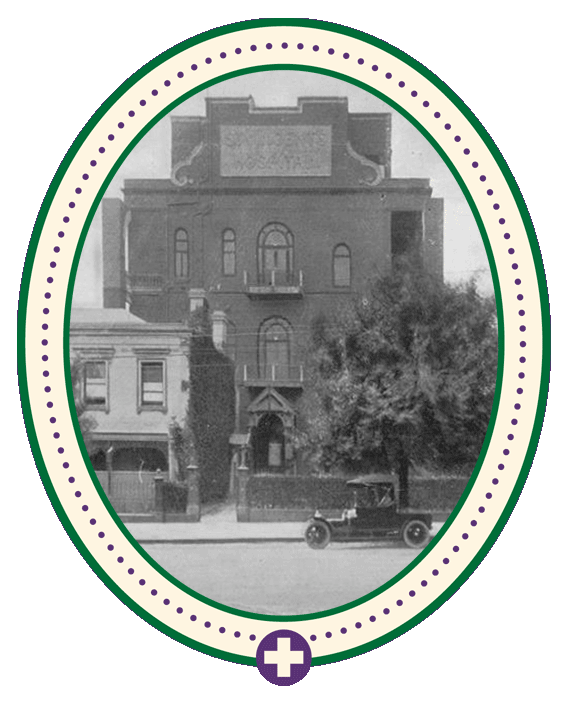

Dr Emily Siedeberg CBE

MB ChB, BSc

In a polite letter to the University Chancellor in 1891, Emily Siedeberg expressed her desire to study medicine at the University of Otago. There was little fanfare, and her medical studies, graduation and residency appear to have all been without incident or controversy. It’s only much later, Siedeberg recounted having had body parts thrown at her during anatomy classes.

In 1905 she was appointed as the first medical superintendent of Dunedin’s St Helen’s Maternity Hospital, a position she maintained until her retirement in 1938.

As a member of the Otago and Southland Patriotic Women’s Association, she travelled to England in 1915 to volunteer her services for the war effort. She spent a period of time with the Scottish Infirmary and returned to New Zealand in 1916.

In 1921, she began a 10 year career as anaesthetist at the Dunedin Dental School. Patient safety was a priority. Siedeberg advocated for the discontinuation of the use of chloroform, and the introduction of the much safer ether.

Siedeberg was instrumental in the establishment of the New Zealand Medical Women’s Association. She actively supported other women wanting to pursue studies and careers in science and medicine, and was a champion of women’s health.

Image: Emily Siedeberg, graduation photo. Image courtesy of collection of Toitῡ Otago Settlers Museum, c1896.

Emily Siedeberg was the first woman to study medicine in New Zealand. Her father, Felix, lobbied the University of Otago and assisted with the admissions process. Siedeberg also wrote directly to the University Chancellor. Despite moderate opposition, her application was successful and she graduated in 1896. Siedeberg then completed a Bachelor of Science, undertook postgraduate studies in Dublin and Berlin, and postgraduate work in Edinburgh before returning to New Zealand.

Images: Letter from Emily Seideberg to University of Otago – courtesy of the Hocken Library, University of Otago, 1891.

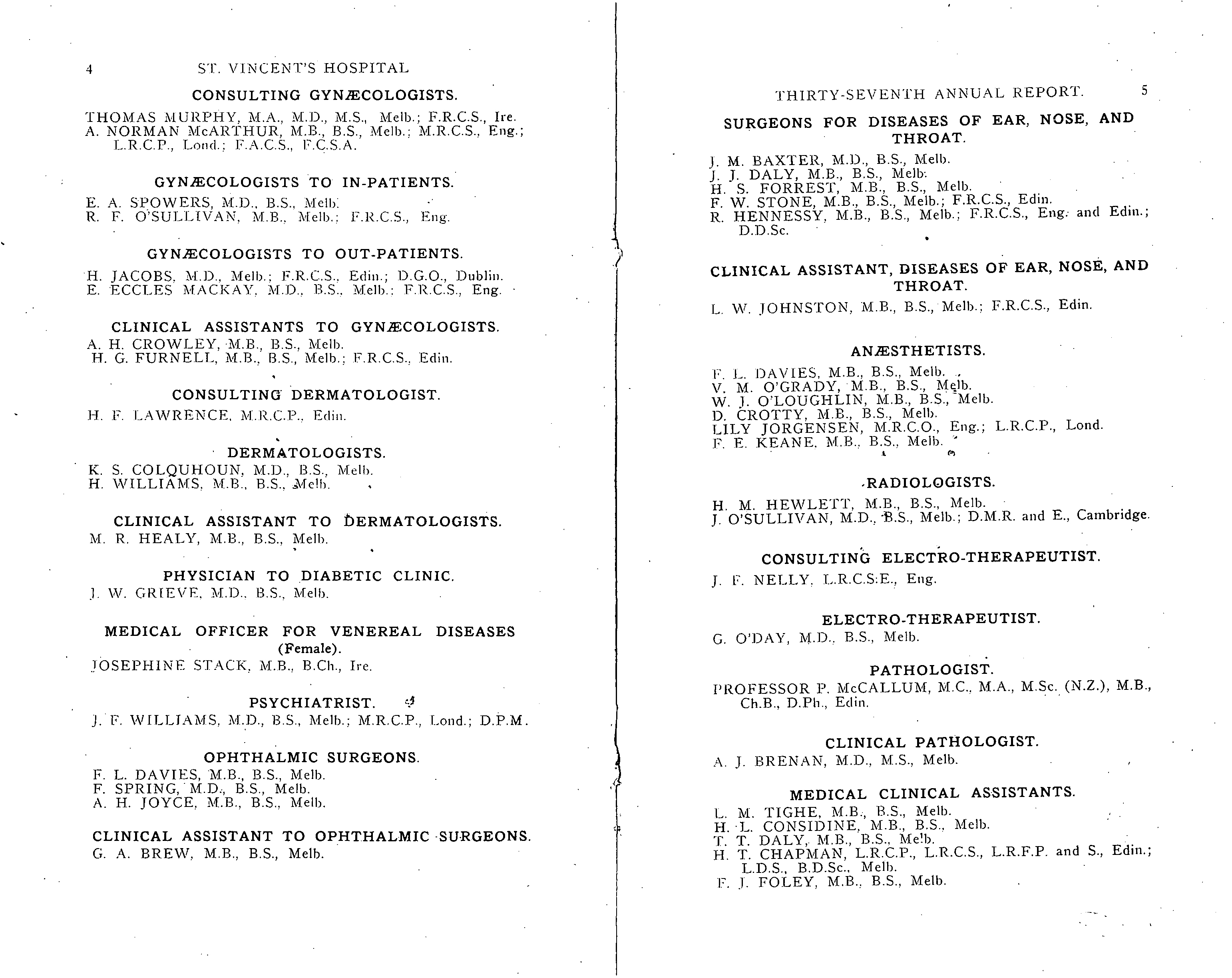

Dr Lily Jörgensen

MRCS, LRCP

Lily Agnes Smith completed a science course at the University of Queensland in 1919. Her scores qualified her for medicine at the University of Sydney. Instead, she moved to Melbourne so she could simultaneously study medicine at the University of Melbourne, and art at the National Gallery of Victoria Art School.

Months shy of completing her medical degree, she married fellow art student Justus Jörgensen, and the pair immediately moved to France to live the bohemian life of artists. She became ill while travelling and was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis.

The pair moved again, this time to London, so Jörgensen could complete her medical studies. She enrolled at the London School of Medicine for Women in 1926. Jörgensen was to be the bread-winner, allowing Justus to concentrate on his art.

In 1928 they returned to Australia. Jörgensen secured an anaesthetist’s position at Melbourne’s St Vincent’s Hospital in 1929, becoming the hospital’s first woman anaesthetist. A severe relapse of multiple sclerosis saw her resign in 1933. She moved into private practice, closer to home, with a focus on contraception and psychoanalysis.

In supporting her husband’s art practice, Dr Lily Jörgensen also supported the building and development of Australia’s oldest artists’ colony, Montsalvat.

Lily Jörgensen’s appointment as an anaesthetist at St Vincent’s Hospital was recorded in the 1930 – 1931 annual report. Although she resigned from the position in 1933, she was the first woman appointed as an anaesthetist at St Vincent’s Hospital, Melbourne.

Image: St Vincent’s Hospital Annual Report 1930 – 1931. Image courtesy of St Vincent’s Hospital Archive.

Dr Helen Mary Mayo OBE

MB BS, MD

Helen Mayo was a driving force in the dramatic improvement in women’s and children’s health that occurred in the first half of the 20th century.

At 17 she began studying arts at the University of Adelaide. Two years later, she transferred to medicine. In 1902 she became the university’s second woman to graduate from medicine.

After graduation she travelled to the UK, where she completed a course in tropical medicine and gained valuable experience in midwifery and other aspects of women’s and children’s health care.

Returning to Adelaide in 1906 Mayo worked as Honorary Anaesthetist at the Adelaide Children’s Hospital. She also set up a private practice specialising in midwifery and women’s and children’s health.

The remainder of her career was dedicated to women’s and children’s health.

Another great interest was disease prevention. Mayo served as clinical bacteriologist at Adelaide Hospital in 1911 and later established its vaccine department. She was also pivotal in the formation of the South Australian Medical Women’s Society, formed in 1927.

In 1926, Helen Mayo was the first woman awarded MD by the University of Adelaide. She gained her doctorate with a thesis on biological therapy by administration of vaccines.

Image: Helen Mayo, graduation photograph, c1902. Image courtesy of University of Adelaide Archives.