Anaesthesia in Australia

and New Zealand

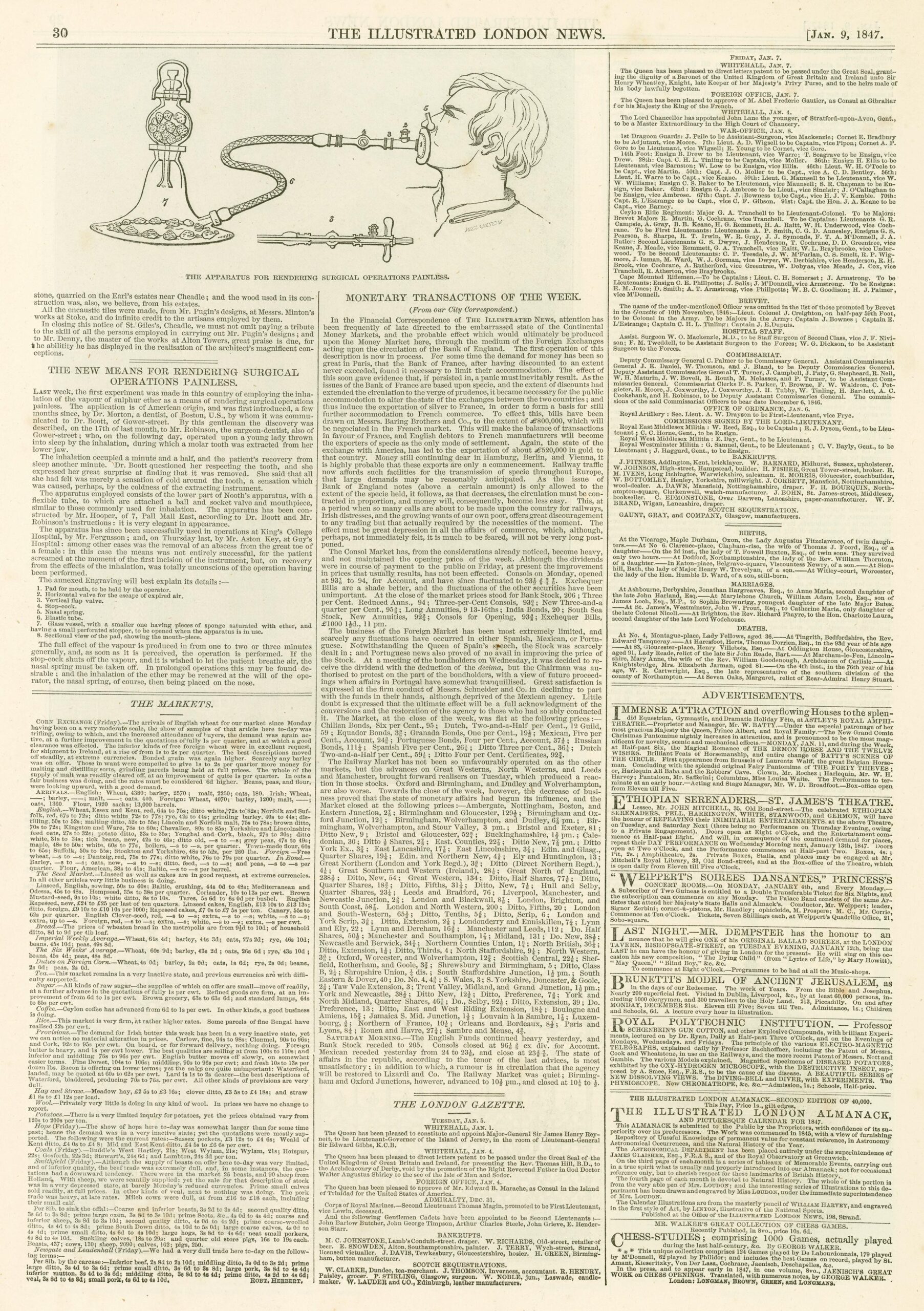

Here in Australia, newspapers were the main method of rapid communication. Railways had not yet been constructed in Australia. The January edition of The Illustrated London News arrived in Australia via ship in May 1847. This edition contained a report on the successful use of inhaled ether to produce painless surgery. As the title reveals, The Illustrated London News was quite advanced for its time and was the first newspaper to feature picture images.

Thanks to an image of the apparatus featured in the article, Sydney dentist John Belisario and Launceston physician William Pugh independently created inhalers and performed procedures using ether in early June 1847.

Both were able to produce a state of insensibility to pain in their patients. Journalists were in attendance, ensuring rapid publicity.

On the morning of 27 September that same year, an unknown prisoner from Wellington Gaol (in Wellington, New Zealand,) had a tooth extracted. Optician James Marriott designed and created the inhalational device and administered ether during the procedure. The morning’s activities were a dress rehearsal for the main event. Māori chief, Hiangarere was scheduled to have an operation that afternoon. A three-pound (1.36 kilogram) tumour was successfully removed from Hiangarere’s shoulder, without causing him any pain.

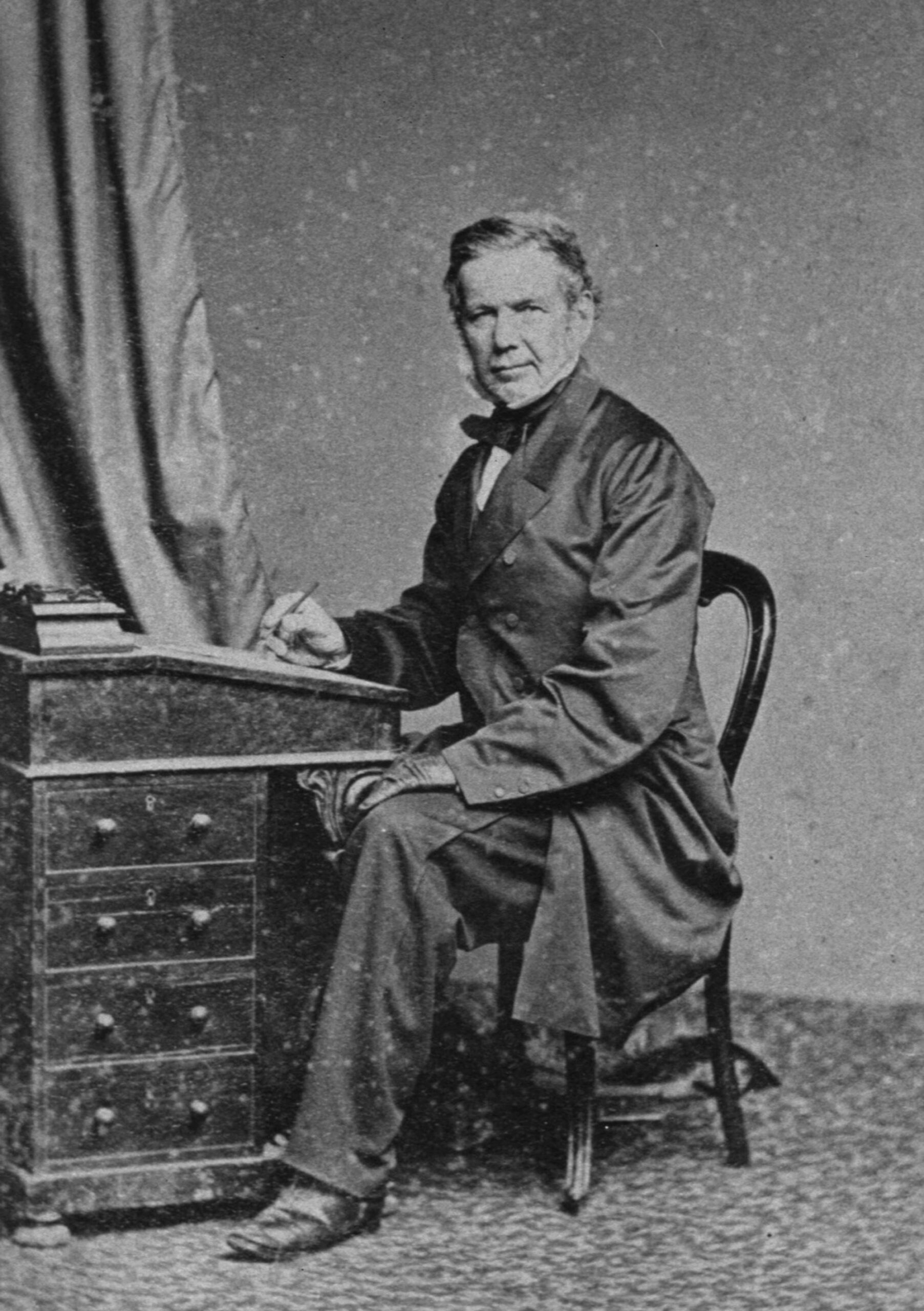

David John Thomas, initially a ship’s surgeon, was the first to introduce ether anaesthesia in Victoria in August 1847.

After administering ether to his patient, he painlessly and successfully amputated the forearm of a patient injured in a shooting accident.

Image: David John Thomas, Courtesy of the Royal Melbourne Hospital, RS346

Pugh’s and Belisario’s original inhalers did not survive. This replica is based on a description of William Pugh’s inhaler which appeared in The Launceston Examiner on the 9 June 1847. As in earlier devices, the sea sponge made up a critical part of the sedation process. It was soaked in ether and placed inside to increase the surface area for evaporation.

Image: Replica, Pugh’s inhaler, Geoffrey Kaye Museum of Anaesthetic History, VGKM4574

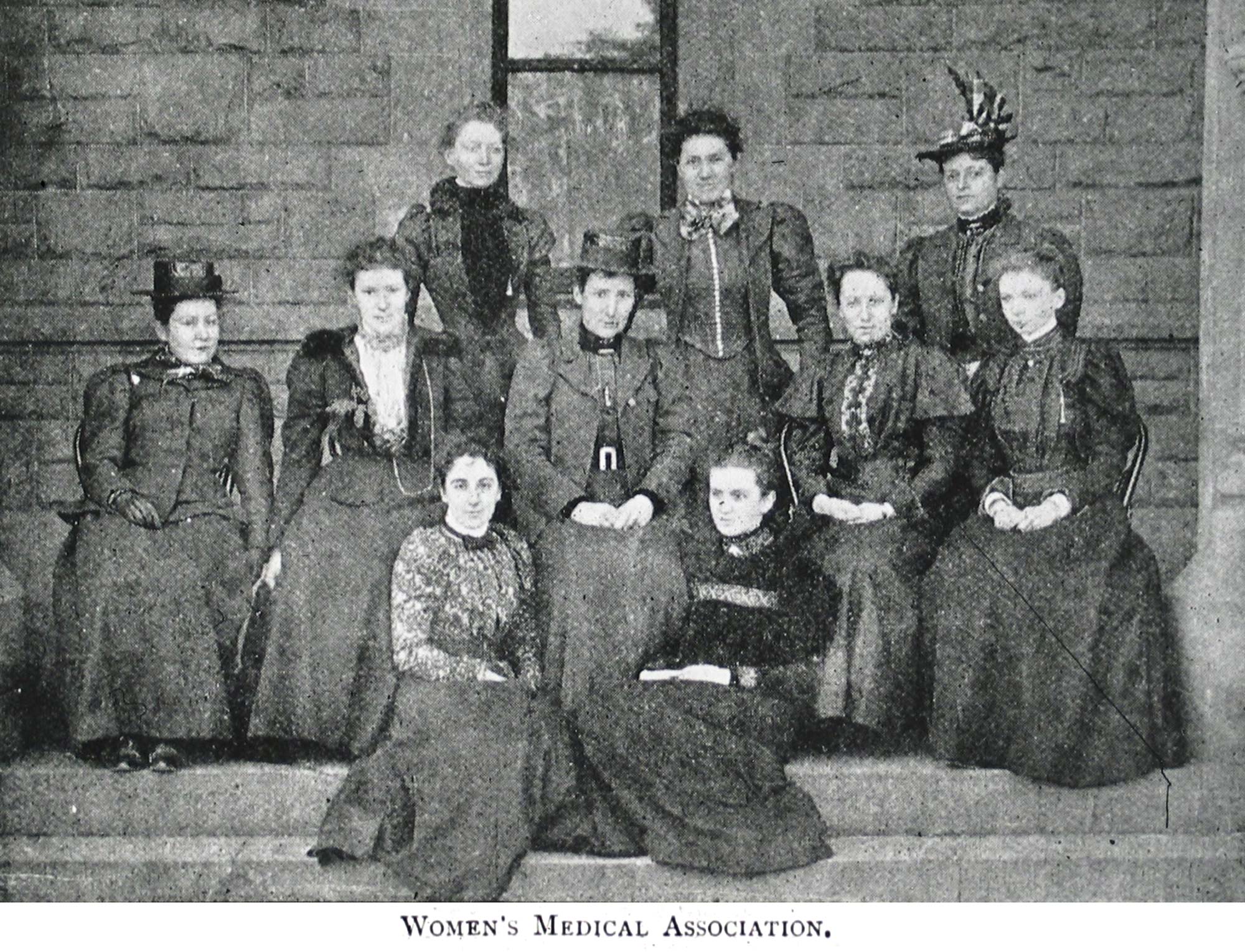

This photo shows some of the first female doctors who faced numerous challenges to be accepted to study Medicine at University of Melbourne. Janet Greig was the first female anaesthetist in Victoria and was appointed Honorary Anaesthetist in 1900 at the Queen Victoria Hospital (known later as the Royal Melbourne Hospital). She was a busy woman, also dedicating her time for the Melbourne General Hospital as the Honorary Assistant Anaesthetist.

Standing (back row) Janet Greig, Constance Stone, Lilian Alexander; Seated on chairs: Amy de Castilla, Emily Mary Page Stone, Helen Sexton, Clara Stone, Jean Greig; Seated on steps: Alfreda Gamble and Bertha Main.

Image: Members of the Victorian Medical Women’s Society, 1896, Courtesy of the Medical History Museum, Faculty of Medicine, Dentistry and Health Sciences, The University of Melbourne, 2024, MHM02919

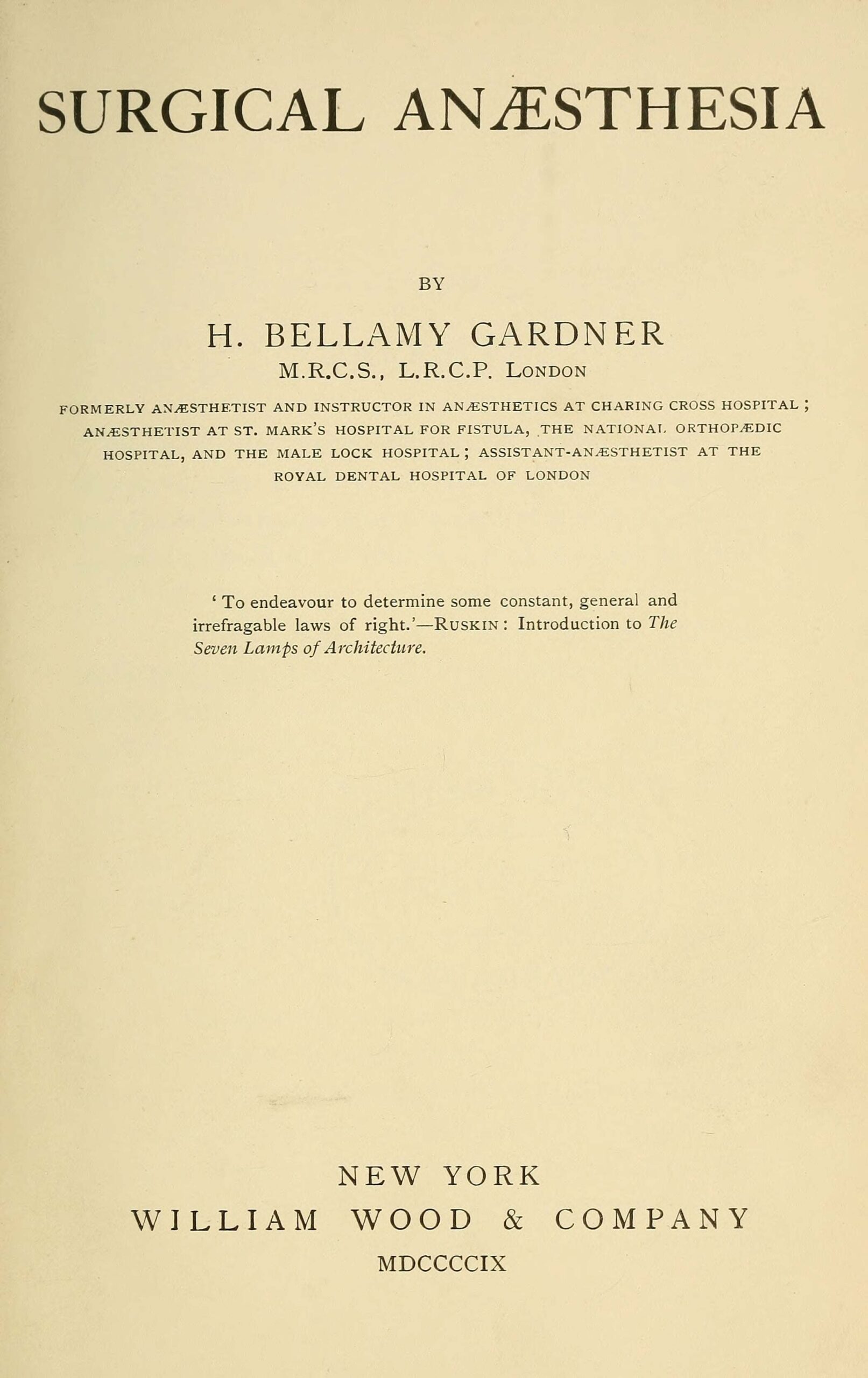

Harold Bellamy Gardner, a physician and anaesthetist at the Charing Cross Hospital in London, advocated for mandatory anaesthetic training for medical students. He contributed to the growing body of knowledge by writing and publishing one of the earliest textbooks in 1909.

Image: Surgical Anaesthesia, by H. Bellamy Gardner, 1909, Wellcome Collection

Image: Bellamy’s mask, Geoffrey Kaye Museum of Anaesthetic History, VGKM4522

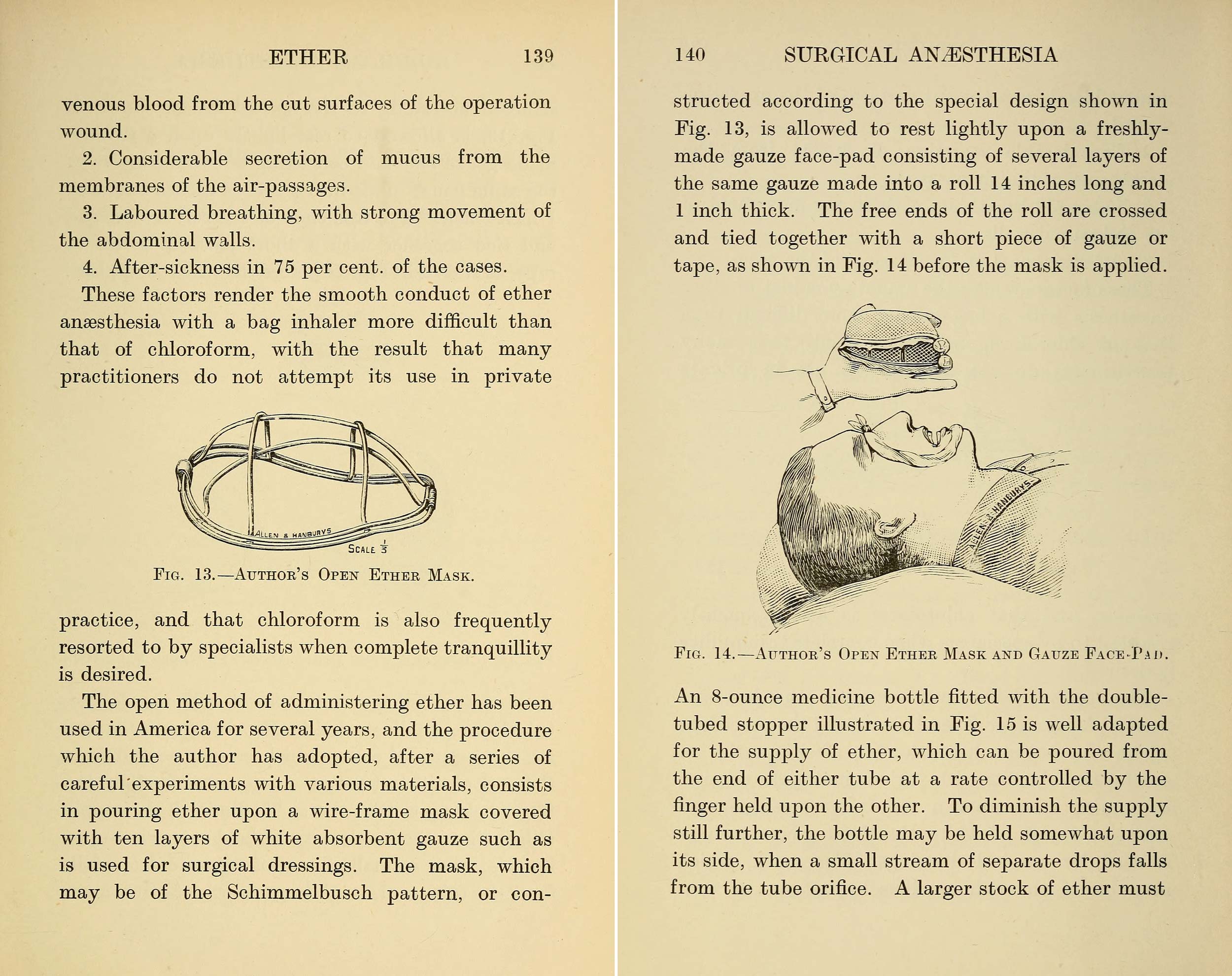

Harold Bellamy Gardner identified several problems with closed ether inhalers. To accommodate these flaws, he designed a mask for ether administration via an “open” method. The illustration from his book shows his wire-frame mask covered with layers of gauze. He recommended rolling additional layers of gauze to construct padding over the eyes and around the nose and mouth to make it more comfortable for the patient. His ether bottle dropper could be inserted into any bottle of ether or chloroform.

Image: Bellamy Gardner’s ether mask, gauze face pad and dropper illustration, p139 – 140, Surgical Anaesthesia, by H. Bellamy Gardner, 1909, Wellcome Collection

Ethyl chloride became a common anaesthetic at the beginning of the 20th century. Different companies producing the anaesthetic competed with one another and designed colourful packaging.

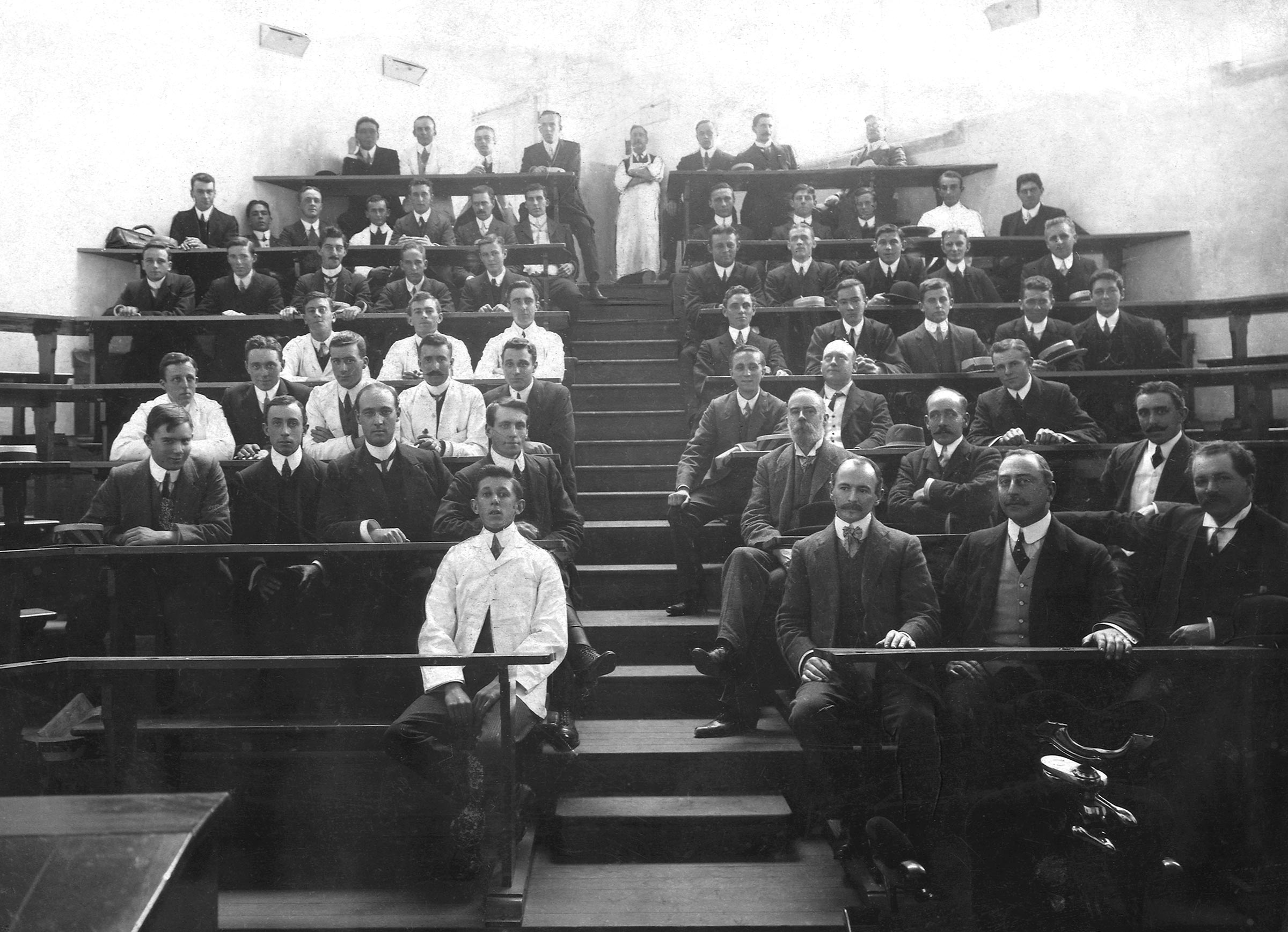

Image: Staff, honoraries, and students, lecture theatre, Australian College of Dentistry, Spring Street, 1907 – 1908, Courtesy of the Henry Forman Atkinson Dental Museum, Faculty of Medicine, Dentistry and Health Sciences, University of Melbourne, HFA4022

Fifth row, Left Side: George Parrett (2nd from left)

Ethyl Chloride, Methyl Chloride & Ethyl Bromide (Somnoform)

Due to ethyl chloride’s unpleasant odour and short duration of potent action, doctors and chemists developed modifications. Somnoform, a blend of various drugs, was introduced in 1901 by Georges Rolland – Director of the Dental School of Bordeaux, France. Somnoform’s brief popularity reached Australia and George Parrett, a graduate in Dentistry from the University of Melbourne in 1912 created this inhaler to be used for somnoform. The ill-fitted wide mask and wide mount for a re-breathing bag must have been uncomfortable for patients.

Image: Somnoform, Bellouard Freres, Dufilho & Co., Geoffrey Kaye Museum of Anaesthetic History, VGKM4362

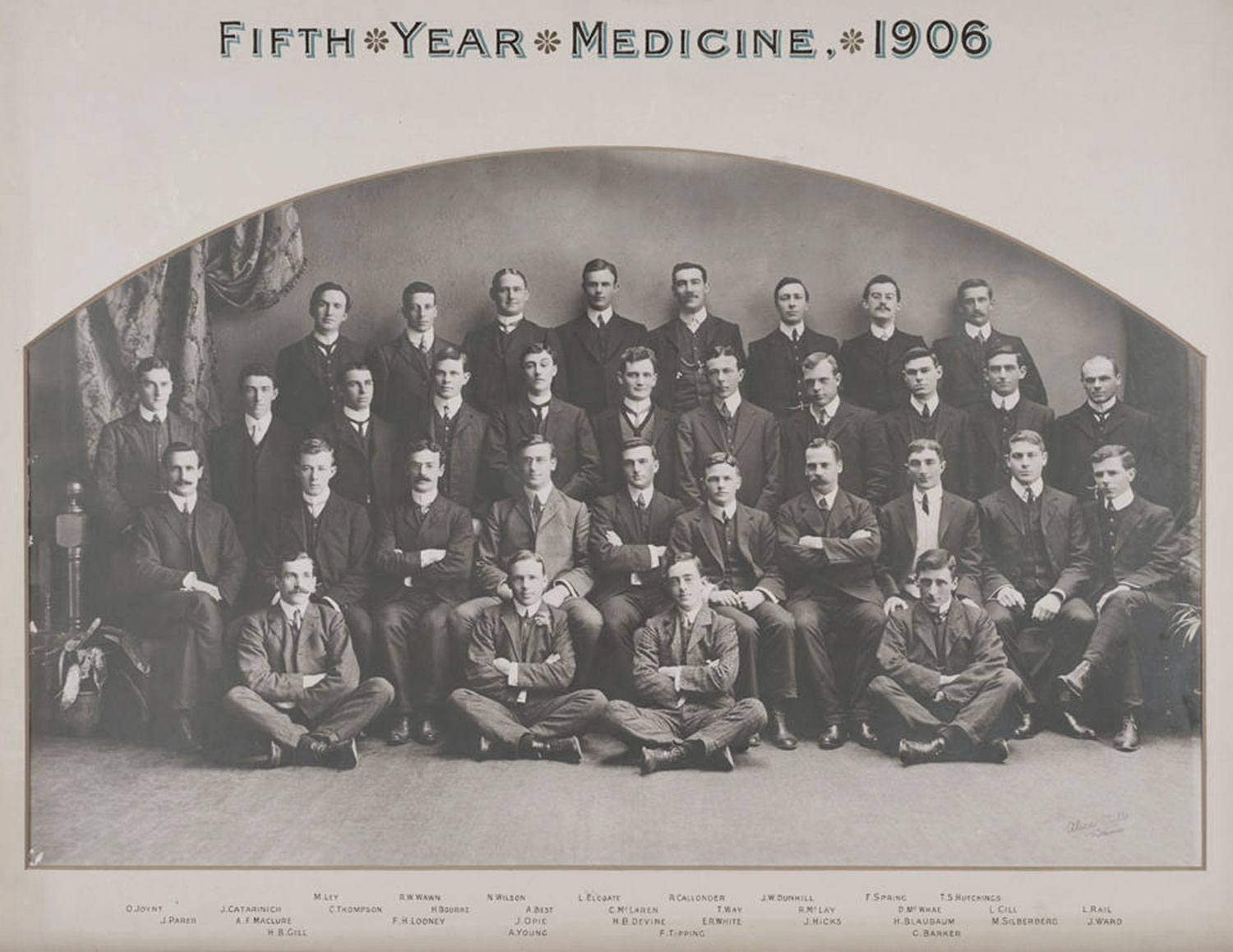

For its first fifty years of modern use, anaesthesia was largely administered by untrained personnel such as medical students, nurses, and hospital porters. They administered this anaesthesia under the direction of the surgeon. Anaesthesia was eventually taught as part of a medical degree, but each student had only to administer six successful general anaesthetics to become proficient. This certificate of proficiency from 1906 was issued to Dr. Montiefiore David Silberberg from the University of Melbourne. The brevity and simplicity of the document captures how little-appreciated the practice of anaesthesia was then when compared with its professionalisation now.

Image: Certificate of proficiency, 1906, The University of Melbourne, Geoffrey Kaye Museum, VGKM5046

Rupert Walter Hornabrook was Australia’s first full-time specialist anaesthetist. Hornabrook regularly acted as his own research subject. While investigating the degrees and stages of anaesthesia, he self-administered ether with a Parrett’s nasal inhaler in front of an audience. While Hornabrook was anaesthetised, a colleague made and sutured a two-inch incision in his forearm. Hornabrook also allowed other doctors to anaesthetise him for research purposes, thereby becoming the research subject and patient. Monitoring during these experiments provided valuable information regarding pulse, blood pressure and other vital functions.

Images: Photographic album of Dr Rupert Hornabrook, 1913, Darge Photographic Company, Geoffrey Kaye Museum of Anaesthetic History, VGKM6580

To continue your journey into the history of anaesthesia explore our other exhibitions –

Trailblazers & Peacekeepers; Rare Privilege of Medicine;

Restoring the Apparently Dead; From Snake Oil To Science;

Pain & Progress; Djeembana Whakaora