Every year we change out one section of the exhibition space to create a new display. The topics are many and varied, and it’s a lot of work, but we think it’s worth it. The museum is a very small space and visitors shouldn’t ever feel they’ve seen everything we have to offer.

It started out as one thing and quickly became something else.

When we put together Trailblazers & Peacekeepers in 2015, we worked with the incredible design company Three’s a Crowd. They’d worked in other museums but this was their first foray into a medical history museum and they were just as excited as we were. They pointed out that pharmaceutical labels of years gone by were often a thing of beauty. Not only did they tell the consumer what they were, they often did so within the overarching art & design movement of the time.

We’d already noticed that but their enthusiasm suggested there could well be an exhibition looking specifically at the labelling, from a typographic perspective. We still think there’s scope for an exhibition like that, it’s just not what we did.

During the research phase, we were reminded how the makers of Nurofen got themselves into a bit of strife with their targeted pain relief marketing strategy. There was suddenly a lot of publicity about the legal proceedings and just as the exhibition launched, they were fined $1.7m for misleading consumers. In addition, I’d spent a day or two at home feeling a little unwell. The recommended course of treatment was some couch time and really, really bad daytime TV. Many of the so-called beauty products advertised had been trialled on 14 or so volunteers with one person experiencing a positive, self-reported outcome. They were labelled “clinically proven”.

You don’t need to be conducting clinical trials to understand the term “clinically proven” seems a little like pseudo-science when only 14 people were involved to begin with. Suddenly, we had our exhibition – From Snake Oil to Science: the development and labelling of pharmaceuticals for the treatment of pain.

We began with a 12th century recipe for pain medicine that apparently came from the Vikings. It was said to be able to produce a sleep that would allow one man to be cut by another man without feeling a thing. The ingredients were listed: hemlock, opium, henbane, lettuce, pig’s bile and vinegar, were mixed with wine to create a drink called dwale. An impressive set of ingredients, although some were a little mysterious (lettuce?). The effect was some sort of anaesthetic state and definitely paralysis but the downside was that it could be (and was) fatal.

By investigating the ingredients of dwale we were able to see the development of modern pharmaceuticals from their botanical origins. Information for preparing hemlock for medicinal purposes were included in the British Pharmacopoeia until 1934, despite its deadly reputation and being notoriously difficult to prepare and store. Contemporary bronchodilators may have had their origins in henbane or belladonna. Use of opium can be dated back to the beginnings of time itself with opium seeds found in Neolithic archaeological excavations. Opium is the basis of so many modern pain medications.

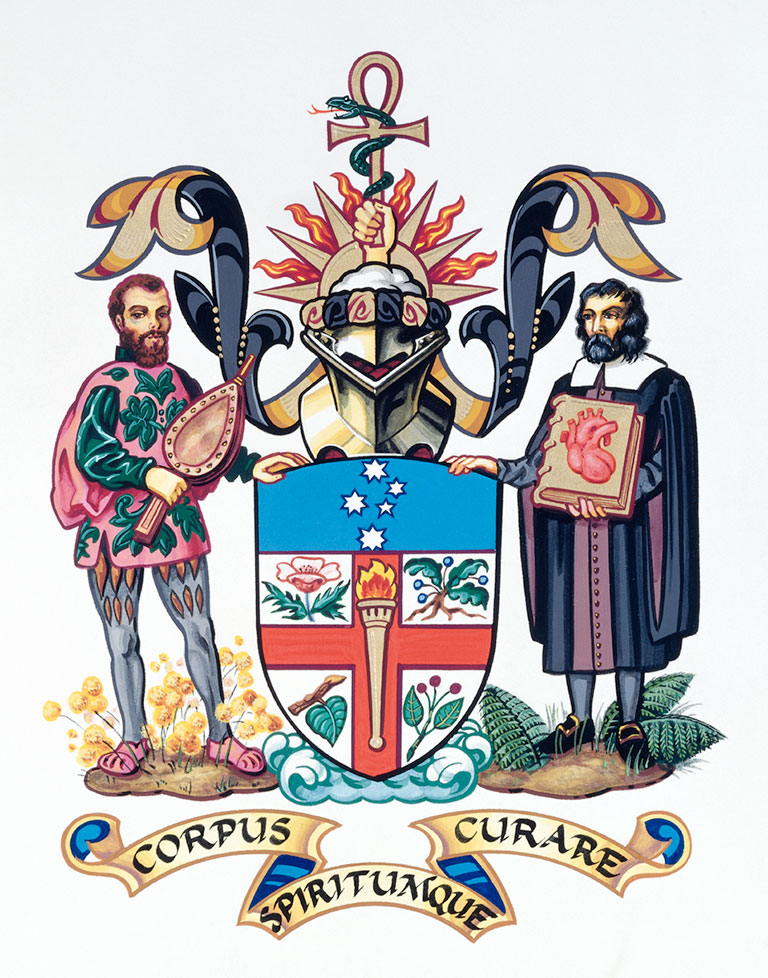

We also wanted to have a look at the College coat of arms. There are four botanicals on the shield and they each have an important reason for being there. The two on top, opium and mandrake, represent the “old world”; a time when medicine was as much superstition as science. The two in the lower half, curare and coca leaf with berry, represent the “new world”; the transition of medicine to science.

Briefing the designers

Through a 21st Century lens, it’s easy to view the 19th century as quite literally awash with opium, morphine and cocaine. Cocaine was even an ingredient in some wines, one of which, Vin Mariani, was endorsed by Pope Leo XIII. The cocaine level probably wasn’t very strong but the whole idea seems a bit wacky today.

While we were certainly looking at the scientific development of pharmaceuticals, it would have been foolish to try to escape or ignore the fact that the Victorians were functioning in something of an opium haze. We wanted to catch some of that vibe in our visuals. At first we talked about the look and feel of the latest Alice in Wonderland film or the colour scheme of a Howard Arkley painting, something that would suggest an altered state of mind.

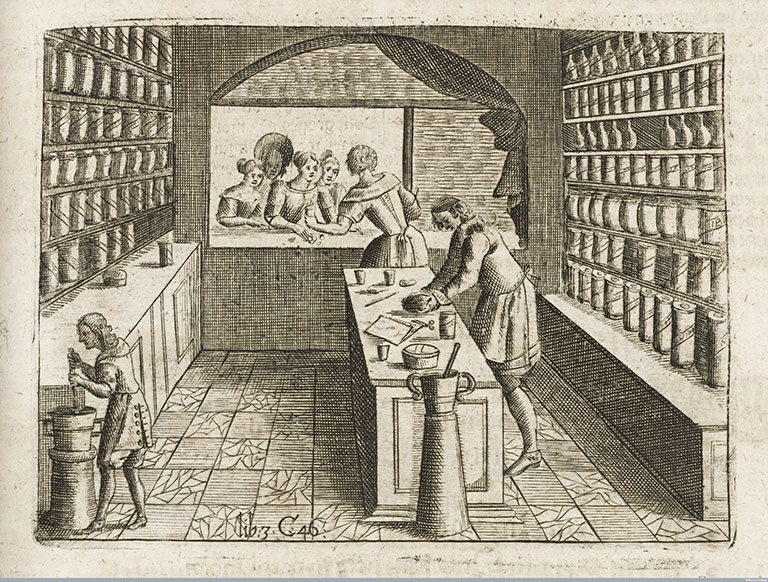

In the end, we toned that down, although it is still the most colourful display in the museum. We have the pinks and greens of botanical drawings, the pinks and greens of Andreas Vesalius from the College coat of arms and the beige coloured paper of a 1902 department store catalogue with muted text. One of the real gems from the designers is a lenticular wall, featuring a reproduced 18th Century print from the rare book collection at the Wellcome Library, an incredible resource for anybody looking for information or images. No matter how hard we try, we can’t really capture the magic of the wall in a photographic, it really is something to be seen.

Borrowing objects

There are two objects borrowed from other museums. The first is an opium pipe, which looks very homemade, from the Gold Museum in Ballarat. The second is a decanted bottle of Perry Davis’ Vegetable Pain Killer from East Gippsland Historical Society. This was a really interesting medicine, as it was the first one designed and marketed to be a general pain killer. Previously, the pain had been targeted (like Nurofen?) for toothache, backache, or whatever ailment needed relief. This was a general, all-purpose pain reliever. The active ingredient, like all good pain relievers of the era, was opium.

Interestingly, there was no requirement for a list of ingredients back then. Nobody needed to know what was in it and testimonial was often used for print advertising. Two points that would never pass muster today.

The objects on loan are due to go back in a year’s time. But, that won’t mean the pack down of the exhibition. The remaining objects all come from the our own Museum collection and include such curiosities as darts from a Malaysian blow gun used for hunting, a machine that will give you a gentle hit of electricity to help with your “nervous disorders” and some reproduced pharmaceutical advertising. From the State Library of Victoria we were able to source an advertisement for Hoadley’s cough medicine which, until 1954, had heroin as an active ingredient.

Online exhibitions

We decided when we reopened in 2014 that every physical exhibition should also have an online version. Our primary audience extends across the entire landmass of Australia and both islands of New Zealand. It would be unreasonable, and poor practice, to expect the only way people could access the museum would be to physically visit it. In 2015, when we launched Trailblazers & Peacekeepers, the online version was ready to go. This time, with From Snake Oil to Science, it’s taken a little longer. Don’t worry though, as soon as it’s ready to go live we’ll be letting you know about it.